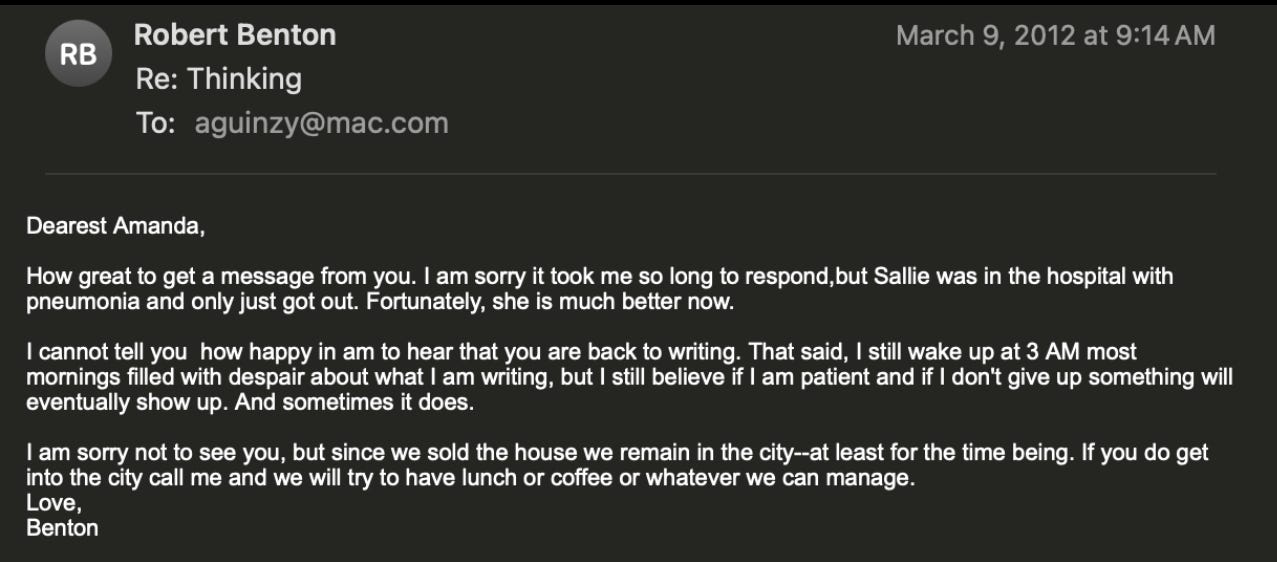

Bonnie & Clyde. Kramer vs. Kramer. Places In the Heart. Nobody’s Fool. Quiet. Jewel-like. Gems. I can’t tell you any stories about how he created these perfect works of high humanist art because we didn’t talk about details, and I didn’t know him then. What I can tell you is that at some point in my mid-thirties, when I was struggling but didn’t realize anyone with a set of eyeballs and a functioning brain could clearly see I was struggling, my Dad told me I should talk to his old friend. We were put in touch, and he asked to see some of my writing. This was early on in the new millennium, and what he actually said, by way of AOL email, was:

Just send me everything.

A seemingly preposterous request, but I was, at the time, in the thick of all this, and had little resistance left, plus, I mean, he was him, so I did it, yes. I sent him short stories from my college thesis and my frantic graduate school years. I sent the too-long, too lyrical screenplay I’d been hired to adapt from a sprawling work of fiction; I sent him editorials I’d begun writing for the scrappy digital start-up mystifyingly named after its Greek lady founder’s Republican ex-husband. I sent him fragments and beginnings and Big Ideas, which I’d never revisit, much less finish.

From behind the door of a small office, he emerged, the first time I went to see him. Lanky, bearded, holding stacks of paper in his arms. It took a solid minute to process that the pages he held out in front of him belonged to me. It seemed Academy Award-winning writer and director Robert Benton had printed out every word I’d sent him, and now he was physically carrying all of it. Pages and pages. Reams of Times Roman inflicted paper, veritably cradled in his elegant arms. He was smiling. I wish I could tell you specifically what he said that day, but the truth is I can’t remember.

What I do recall with visceral clarity is that the whole time we spoke, he looked me straight in the eyes. He did this without any trace of either disappointment or expectation. He looked in a way that made me feel tethered and present. Present in the room and tethered to the world as it was, as though my words, along with my self, were sufficient for both. Revealed but not ashamed. Shown, but not exposed. His gaze was at once encouraging, unflinching, and deeply kind. He met me precisely where I was, and as if he’d known me all along.

A couple of years later I would drive East from where I was staying with my worried mom and stepdad in Water Mill, past the potato fields and horse farms, past the wildflowers gathered in glass vases, clutches of arugula, and squat red tomatoes, past the clapboard stands by the sides of the road, out toward the heavenly stretch of acreage he’d bought for a pittance in the Sixties, out towards the hills that rose and fell near the island’s end.

I remember the quality of that dusky afternoon as it morphed into evening, how the sun was bowing down its head, how the earlier chill of October sharpened against a summer still lingering with humidity and salty air, how the tree branches swayed in the soft breeze as I drove past, along the back roads, mapped by heart, stalwart oak sentinels rooted beneath loam-rich earth, guardians of the periphery, leaves lush and still green, waving travelers toward the water, restlessness and longing slipped off like silk, cast out into the waves along with the fading pink light.

Later, I would sit across from him in a big room that was clean and airy and white. His wife, Sallie, naturally cool and forever beautiful, had greeted me and was now off painting in her studio. Their only son, John, was moving around at a respectful distance, opening and closing cabinets in the kitchen.

Only one thing to do when it’s this bad, he said. Write. Doesn’t matter what. Something. Anything. Every day. You just have to do it. No matter what. Be patient.

Write shit.

I’ve mentioned the clarion call of his instruction before, without naming him.

It would be years. Years until I could practice it. Years before I realized how utterly my own perfectionism was paralyzing me, how the abject fear of failing was doing everything to guarantee it. Burning out each flicker of potential at any hint of a spark. Fraying any loose stitch of progress. My shame was a slick thief dressed all in black, camouflaged so I couldn’t see it. A long con committed by a determined brain over decades in the dark.

It took a lot of time for me to stop listening and really hear him. To understand what he was telling me.

I did, though. Eventually. In fits and starts.

See this?

That’s the bottom of something I’ve been working on for around twelve years. You’ll have to take my word for it, but four hundred forty-one extremely far from finished pages means the lady whose work you’re currently reading has written vast amounts of shit.

—

I delivered a hybrid eulogy/toast to a room full of lovely and remarkable people, splayed out in a blur before me on a late March evening across from Gramercy Park. We’d chosen to celebrate my Dad’s life on his 85th birthday, which was six months following his death. In the middle of a crowded aisle afterward, Benton stood with his arms extended, waiting. Lanky, gentle, smiling. By himself. Just waiting. He shook his head back and forth slowly, and as he pulled me toward him, he softly said,

That was perfect.

You did it, Kid.

—

I tried to find an address so I could write a proper note to him after Sallie died two years ago. We hadn’t been in touch for a long while. I wanted him to know how sorry I was that he’d lost her. I wanted to thank him for all the ways he helped me during all the times he did. I wanted to hold some of his sorrow as graciously as he’d held mine. I wanted to, but the truth is that when I say I tried to find him, I barely did. I kept meaning to. I could have really tried. I could have found him, but I didn’t. And there was a window of appropriateness I talked myself into believing had shut. It hadn’t. Until ten days ago, when my mother called to tell me he was gone, and then it did.

You have a person, don’t you? You’ve been meaning to reach out. You love them. You miss them. You’re grateful to them.

But.

You’re so busy, there is too much else. The world is on fire. You want to and you mean to…

But.

A relative. A mentor. An old friend. Distance comes. There are reasons. At some point, you might’ve heard they went through a…Thing. They lost someone, they got sick, their kid fell into trouble. You didn’t know what to say, too much time has passed now, and you’re sure it will be worse if you stumble back in; you’ll only be an added burden.

Listen to me carefully: It won’t be worse. Your love isn’t a burden. Stumbling is fine. Stumbling is great. Wouldn’t you rather have someone stumble back around? I’m sorry. You mean so much to me. I’m still here.

However much time it’s been, trust me.

Mail the card. Call the number. Write the text. Hit send.

What I’m doing right now is because of him.

Inside the latching grief and twisty gnaw of regret, I write through it. In the morning now, past thick, dirty clouds, in front of a big open window, I write through it. I plant the words down and turn them over. Over and over again. Always hard, sometimes impossible, but it’s better now. Better than when I started.

He never made me feel lost or unlovable, irredeemable, or sick. He just looked, and read, and nodded. He smiled. And he waited. He saw all my pages. Carried them carefully. Held them in his arms and his heart. Turned them over until he found what was worth saving.

Forgive me for not finding you before you left. Until we meet again, sweet friend. I’ll be patient.

Beloved Benton.

I’m keeping all of it.

This is gorgeous and made me weep. Thank you, you are so brave, so talented, and I'm so proud of you for sharing this vulnerable and incredibly meaningful piece of writing. I'm so sorry you lost your friend. Love you.

It must certainly be a relief for one’s grief, dear Amanda, to be able to put it into words in such a gifted, beautiful, moving way… You should write more and more often. Why not a book on your recollections??